Sports researcher Dave Berri had a disagreement with a remark in our recent discussion of Malcolm Gladwell. Berri writes:

This post [from Gelman] contains the following paragraph:

Similarly, when Gladwell claimed that NFL quarterback performance is unrelated to the order they were drafted out of college, he appears to have been wrong. But if you take his writing as stone soup, maybe it’s valuable: just retreat to the statement that there’s only a weak relationship between draft order and NFL performance. That alone is interesting. It’s too bad that Gladwell sometimes has to make false general statements in order to get our attention, but maybe that’s what is needed to shake people out of their mental complacency.

The above paragraph links to a blog post by Eric Loken. This is something you have linked to before. And when you linked to it before I tried to explain why Loken’s work is not very good. Since you still think this work shows that Gladwell – and therefore Rob Simmons and I – are “wrong”, let me try and explain again why Loken’s analysis isn’t something you should be highlighting on your blog.

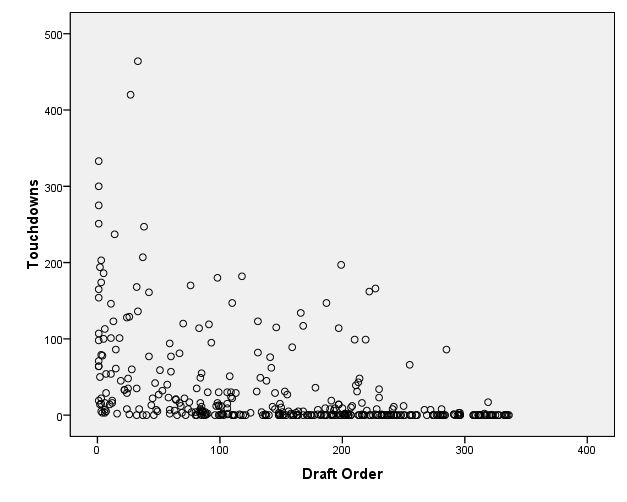

1. Loken begins by looking at the link between touchdowns and draft position. This is the only graph he presents and the only correlation coefficients he presents. This is incorrect for two reasons

a. Touchdowns are a statistic that reflects playing time. We documented in our research that quarterbacks drafted first receive more playing time. This bias needs to be addressed if we are going to assess how well people taken at different points in the draft perform.

b. Touchdowns are a poor measure of performance. They ignore most of what a quarterback does on the field. So this should not be the only measure of performance someone chooses. Such a choice suggests Loken doesn’t understand how to measure performance in football. Given that this research is about how draft position relates to performance, not being able to measure performance is a problem.

2. Loken then offers the following statement: On his blog, Berri says he restricts the analysis to QBs who have played more than 500 downs, or for 5 years. He also looks at per-play statistics, like touchdowns per game, to counter what he considers an opportunity bias.

There are two very significant problems with this statement.

a. This is the blog post he is referencing:

The Inconsistent Quarterback Story Told Again in Less than 3,000 Words

As you can see, I did mention the five year result. HOWEVER, directly below – and I mean, this appears right after I noted the five-year result – I state the following:

Our data set runs from 1970 to 2007 (adjustments were made for how performance changed over time). We also looked at career performance after 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 years. In addition, we also looked at what a player did in each year from 1 to 10. And with each data set our story looks essentially the same. The above stats are not really correlated with draft position.

As you can see, we didn’t just look at results after five years. We did far more than that. Loken, though, failed to see this. And he failed to see this despite the fact it was mentioned in the very next sentences. This suggests that not only is Loken not very good at analyzing this question, he also doesn’t seem willing (or able) to simply read.

b. Loken then says we looked at touchdowns per game, which he calls a per play statistic. Touchdowns per game are obviously not a per play statistic. Touchdowns per play or per pass attempt would be a per play statistic. So again we see that Loken does not understand this subject.

In our research we did look at touchdowns per pass attempt. But again, this is not the best measure. So we also looked at QB Score per play, Net Points per play, Wins Produced per play, the NFL’s quarterback rating, Passing yards per attempt, Interceptions per attempt, and Completion percentage. And again, we looked at this after each of the first eight years of a player’s career as well as what the player did in each of his first ten years.

The attached article – which I have sent to you before – details all of this and indicates that we also do far more than just what I am describing.

Again, when you originally posted Loken’s research, I sent you this article. I also sent you the above link to the blog post I wrote responding to Loken and other writers. And I also sent you this link with even more discussion.

And Yet Another Look at Drafting Quarterbacks in the NFL

Despite all this, you have chosen to argue that Loken’s poorly constructed blog post indicates that Gladwell – and again, therefore Rob Simmons and I – are “wrong”.

Take a step back for a moment and imagine that Gladwell did exactly what you have done. Rather than report the results seen in the academic literature, imagine Gladwell argued that poorly constructed blog posts by uninformed people were sufficient to refute what we see in the academic literature. If Gladwell was doing this, I think you (and Chabris and Pinker) would have a legitimate problem. But Gladwell is not doing this. You and Pinker are doing this. Both of you are relying on very poor analysis from a blog post to refute published research. And you are relying on this analysis to show that Gladwell is “wrong”. Perhaps you might want to re-think your reasoning on this subject.

I replied that I am indeed no expert on the NFL and I thought it would be fairest to post Berri’s remarks directly on the blog. Berri agreed but wanted to further emphasize the way in which I can mislead: my blogging gives an air of authority, and an offhand remark about something I don’t fully understand can be taken too seriously by readers.

In this case, I know Eric Loken and respect his work, so I will tend to go with his views on a topic such as football that I don’t know much about.

In this particular debate, with Dave Berri and Malcolm Gladwell on one side, and Eric Loken and Steven Pinker on the other, my impression is that the key point of contention is whether to look at proportional statistics or career statistics. Berri argues that high draft picks get more playing time and that it’s best to compare scores per play, yards per attempt, etc. Loken argues that by conditioning on the outcome that is total playing time, you’re eliminating much of the effect.

To put it another way: Berri and Loken agree that NFL quarterback outcomes are related to the order they were drafted out of college. The difference, as far as I can tell, is that Berri believes that the observed correlation in the data arises from high draft picks getting more playing time and does not reflect actual differences in performance, whereas Loken believes that the difference in playing time does reflect differences in performance. I think (but I’m not completely sure about this) that Berri is attributing the difference in playing time to some combination of sunk-cost fallacy and actual sunk costs (for example, if you give a QB a big contract and he’s sitting around anyway, the coach might as well put him on the field once in awhile), whereas Loken is making an economics-style argument that, if a QB is getting more playing time, the coach must have a good reason for it (replacement value and all that). Maybe Gregg Easterbrook could weigh in with some Tebow-related thoughts.

From a formal causal inference perspective, I think one would want to study this using some sort of latent-variable model to take advantage of the information from playing time and also the per-play, per-game, and per-season statistics.

In any case, I’m happy to emphasize that I am no expert on football, and I refer you to Berri’s and Loken’s more detailed posts for more on the topic. My offhand comment in a post on Malcolm Gladwell is no substitute for actual research.

Injuries provide a useful quasi-experiment to test these models. To simplify for a blog comment, if 10 4th rounders are backup QB’s one year, of 30 4th round QBs of an appropriate age, and 1 of them gets in for half a season from a QB’s injury, we’d expect him to be at best around the top 15% of active 4th round QB’s. Since he’s playing real games and not just mopping up you just get reasonable statistics. Then you can extrapolate how he would’ve done over a full year. If your model greatly over- or under- estimates his contribution that suggests the way you are handling all the uncontrollable variables is wrong.

No effort to control for the quality of the players on the offense?

Also, Berri doesn’t think the players drafted in later rounds who rarely play because the probably suck should be included for fear of selection bias?

You should have told Berri to shove it if his argument is that his really terrible study is better than a somewhat less terrible study.

Rather than tell anyone to shove it, I’d prefer to submit the question to the hive mind via blog.

The core issue is item #4 in Berri’s rebuttal here: http://wagesofwins.com/2009/12/06/the-inconsistent-quarterback-story-told-again-in-less-than-3000-words/. Berri is testing the question “Among quarterbacks who play in the NFL, is draft position related to success?”, and he finds the answer is no. That’s an interesting result, but it’s NOT THE SAME QUESTION as “Is draft position related to the success of NFL quarterbacks?”. Here, Berri argues that since we have no results for NFL quarterbacks who can’t play, there’s no way to know if a benched quarterback is the next Peyton Manning or Spergon Wynn. That’s a pretty strong belief. Isn’t this a perfect test case for a selection model, where x criteria predict playing time (or draft position), and x + z criteria predict performance?

To Berri’s credit, he links to this: http://www.advancednflstats.com/2010/04/steven-pinker-vs-malcolm-gladwell-and.html which is a pretty thoughtful way to look at the selection issue. He finds there is a relationship between draft position and NFL performance. Berri rebuts here: http://wagesofwins.com/2010/05/26/and-yet-another-look-at-drafting-quarterbacks-in-the-nfl/, claiming that a) Burke should have included different years of data in his sample b) that the more quarterbacks play, the better they get, so you shouldn’t look at low attempts quarterbacks c) if you restrict your analysis to the top 60 picks, the Berri story remains true

My thoughts: Berri hit on an interesting result and then stretched it too far. He’s arguing that players who don’t play would perform similarly (in the aggregate) to players who do play, if those non-players got enough playing time. But the evidence for that supposition is lacking. And I say that as a Browns fan, who watched an undrafted free agent (Brian Hoyer) go 3-0 in his starts while a first round QB pick (Brandon Weeden) lose every one of his starts this season — because even though Tim Couch was a disappointing QB, he was still better than Spergon Wynn).

Some good news: with the new pick-related salary caps, there are fewer sunk costs for draft picks (they’re still there, but there are no longer and Bradford/Stafford $50 million contracts for early QB picks). So there may be less noise in the data going forward — of course, it’s possible GM’s will get better at evaluating talent!

I think I agree with your thoughts on it. To put it another way:

“Some late-round/undrafted QBs get the short end of the stick (perhaps) because of sunk cost fallacies with high draft picks” is reasonable given the data.

“There is no relationship between draft order and performance” is a step too far and takes some researcher decisions (the dicing of the data) to get there.

Berri’s argument is a little strange since the facts he describes are completely consistent with Loken’s claim (and conventional wisdom) that earlier draft picks tend to be better QBs. Playing time is determined by 1) the player’s ability as shown in past games and practices (practices are unobservable to the researcher) and 2) the coach & GM’s (potential) discrimination against late draft picks (and then some other factors as well, probably).

If the coach chooses playing time only looking at the player’s ability (again, as shown in practice), you’d see no connection between draft order and performance after conditioning on playing time (the term for this is a ‘mediating variable,’ right?). This point I think was made in Loken’s post.

If the coach factors draft position into playing time decisions, we’d expect to see that later draft picks perform *better* than earlier draft picks, conditional on playing time. I don’t do labor economics, but I think this sort of result shows up all the time in the literature on estimating effects of discrimination.

Obviously there are other statistical issues that I’ve ignored—fit within a system, teammates, etc—that make estimating performance difficult, but if you can estimate it well, the facts Berri’s described would imply that coaches aren’t biased in favor of early draft picks and then the playing time estimates imply that early draft picks tend to be better QBs than late draft picks.

If someone wanted to do a real research paper on this subject, it might not be hard to look at playing time decisions made after a coach or GM were replaced—presumably the new management would be less biased in favor of the current roster and if their playing time decisions were systematically different than coaches that haven’t been replaced recently (or than the previous management) that could be evidence of bias towards draft position. Then the statistical issues I glossed over earlier start to matter a lot, though.

Good grief that’s a blast from the past. Yes, I can read, although when I saw this post today I kind of wish I couldn’t. So just two quick points –

— I will not pretend to be an expert regarding football or sports economics and the blog posts do not represent a line of research. Today there are many sophisticated sports simulation algorithms and handicapping tools and modeling approaches. Josh Millet and I simply wrote some posts in reaction to an assertion by Gladwell that there was essentially no connection between draft order and NFL performance. Remember that Gladwell wrote: “a prediction, in a field where prediction is not possible, is nothing but a prejudice.” That seemed at the least to be an overstatement. I’ll stand by my assertion that total productivity is a relevant outcome in many employment settings, and something worth predicting. And specifically I’ll stand by my opinion that regressing out total productivity to arrive at efficiency stats risks throwing out some of baby with the bathwater (statisticians are allowed to consider the impacts of throwing out some of the variance). I understand that there are questions about over paying salaries, and irrational allocations of resources for the highest picks. But to say “prediction is not possible”? I have to disagree and I think the information reflected in the draft order of quarterbacks is germane. I also think there’s a reason that kids in the schoolyard alternate picks to create two teams.

— and FWIW a shout out to Matt McGloin, a Penn State alum who went undrafted in 2013 and yet sits second on the Oakland Raiders depth chart. He earned this position over two drafted quarterbacks who were much bigger investments by the team. Clearly when an employee shows up for work there is a wealth of new information on which to base evaluations. That doesn’t mean that McGloin was only passed over on draft day due to a prejudiced and random process. It’s the kind of thing that happens when the correlation isn’t 1.0.

So the new GMC Behemoth with it’s 50 gallon gas tank can go 500 miles before needing a refill, while the new Nissan Sprite with it’s 5 gallon gas tank can go 250 miles before a refill. Your predictive fuel cost model will be worthless if you only base it only on ‘total productivity’, in fact you will get exactly the wrong answer. Prediction is possible, but useless.

I have to hire 30 sales people for my company, the first 15 that I hire, the ones I think are the best candidates, are given phones, e-mail, expense accounts, etc. The second batch of 15 get nothing, they sit in a room all day and stare at the clock. When the first batch of hires outperforms the 2nd batch, that is not proof of my ability to predict who the best sales people will be. Anyone should be able to predict an outcome that they have control over.

Kids alternate picks in the schoolyard to be fair. Obviously IF you can pick who is a better player there would be an advantage in picking all of your players first. However, believing you can pick who the better player is and actually having that ability are entirely different things. No one doubts that NFL coaches and GM’s think they can identify talent, the question is can they ?

So it’s still about whether the lack of playing time is related more to the sunk-cost fallacy or more to information not available to us (those outside the specific team). Your situation assumes the former, but I don’t think the latter possibility is ruled out at all.

I like the idea at looking at coaching changes to try to pry these apart; I also would think looking at players changing teams might be useful too. There’s a whole lot of “other stuff” that comes with doing that (Why are they changing teams? What’s the personnel situation at their new team?) that would have to be addressed though.

I am with @TBW here.

@Eric Loken: You offer a fallacious: “total productivity is a relevant outcome in many employment settings,” Yes, but the playing field is more level. All analysts, chefs, engineers etc. hired together get roughly the same access to equipment and working hours.

My question to you is, even assuming you are right, and the early draft picks are indeed inherently better; now why then does their performance metric degrade to close to the average once they are normalized for playing time? Can you postulate any mechanism for this to happen?

Okay Rahul, I’ll bite one last time but I tried to make it clear above that my perspective is one of a fan and methodologist, and not specifically a sports economist. That said, here’s my take on your question.

First off, predicting the relative success of professional football players is going to be very difficult no matter what the performance metric. You have a narrow, highly selected pool of elite athletes. (One of my favorite teaching examples that I blogged on years ago is that the four rounds of a PGA golf tournament appear to have almost zero reliability, and yet there can be no more valid measure of golf ability than golf score – it’s obviously a problem of restriction of range in the PGA). Adding to the difficulties, the new players expected to be best go to the worst teams, and careers in professional football are extremely short on average. Right off the bat you have a terrible setting for prediction.

The collective wisdom of the “market” as it were in assessing new talent is revealed more or less in the draft order. My belief is that that collective wisdom can achieve some degree of reliability in rank ordering the value of the new talent. I count it as supportive evidence that despite all the measurement difficulties I layed out above, there are substantial correlations between draft order and various measures of total success on the football field.

Some people would like to sweep away those correlations and say they are attributable solely to the fact that the higher draft choices get to play more. That’s fine and clearly a viable approach that could be empirically validated. Comments here have suggested ways to tease apart ability and opportunity. My a priori opinion is that conditioning on playing time actually eliminates what might be the best signal in a very difficult prediction situation. I understand the desire for efficiency scores. But there are lots of examples of this kind where it is debatable whether or not to condition on the total. Should scholars be evaluated on total citations, or citations per paper? Total grant money, or dollars per grant? Should a running back be evaluated on total yards for the season, or yards per carry? In each case something is lost in the conditioning.

So my “mechanism” boils down to measurement. The measurement setting is tough to start with, probably the most measurable outcomes are those related to total production, and by the time you condition on time played and declare total production off-limits as an index of success you’re likely left with very weak signal indeed. I’m not saying that the per-play stats are never interesting. I just find it weird to discard the strong correlations with total productivity. Life in the NFL is brutal and short. when one quarterback starts 60 games and another starts 10, I honestly think it strange to say they can only be compared on a per-game (or per-play if you prefer to divide by a bigger number) basis.

I again need to say that I don’t research this topic and that my expertise is in measurement and assessment. The only reason I’m involved in this debate at all is that four years ago we wrote some blogs questioning Gladwell’s assertion that prediction was not possible in football. Then Pinker reviewed Gladwell’s book, and then Gladwell replied by doubling down on the football point. Then Pinker said that our blog was one of three sources that influenced him. And for some reason it’s all still churning along four years later.

Football is actually a really difficult sport to study. Has there been research on other sports with draft picks, like basketball, that perhaps have easier outcome metrics to measure? Or what about the NHL? This is a very counter-intuitive hypothesis, and I think that this is a good example of when strong claims require strong evidence.