It all started when I was reading Chris Blattman’s blog and noticed this:

One of the most provocative and interesting field experiments I [Blattman] have seen in this year:

Poor people often do not make investments, even when returns are high. One possible explanation is that they have low aspirations and form mental models of their future opportunities which ignore some options for investment.

This paper reports on a field experiment to test this hypothesis in rural Ethiopia. Individuals were randomly invited to watch documentaries about people from similar communities who had succeeded in agriculture or business, without help from government or NGOs. A placebo group watched an Ethiopian entertainment programme and a control group were simply surveyed.

. . . Six months after screening, aspirations had improved among treated individuals and did not change in the placebo or control groups. Treatment effects were larger for those with higher pre-treatment aspirations. We also find treatment effects on savings, use of credit, children’s school enrolment and spending on children’s schooling, suggesting that changes in aspirations can translate into changes in a range of forward-looking behaviours.

What was my reaction? When I saw Chris describe this as “provocative and interesting,” my first thought was—hey, this could be important! I have a lot of respect for Chris Blattman, both regarding his general judgment and his expertise more particularly in research on international development.

My immediate next reaction was a generalized skepticism, the sort of thing I feel when encountering any sort of claim in social science. I read the above paragraphs with a somewhat critical eye and noticed some issues: potential multiple comparisons (“forking paths”) and comparisons between significant and non-significant, also possible issues with “story time.” So now I wanted to see more.

Blattman’s post links to an article, “The Future in Mind: Aspirations and Forward-Looking Behaviour in Rural Ethiopia,” by Bernard Tanguy, Stefan Dercon, Kate Orkin, and Alemayehu Seyoum Taffesse. Here’s the final sentence of the abstract:

The result that a one-hour documentary shown six months earlier induces actual behavioural change suggests a challenging, promising avenue for further research and poverty-related interventions.

OK, maybe. But now I’m really getting skeptical. How much effect can we really expect to get from a one-hour movie? And now I’m looking more carefully at what Chris wrote: “provocative and interesting.” Hmmm . . . Chris doesn’t actually say he believes it!

Now it’s time to read the Tanguy et al. article. Unfortunately the link only gives the abstract, with no pointer to the actual paper that I can see. So I google the title, *The Future in Mind: Aspirations and Forward-Looking Behaviour in Rural Ethiopia*, and it works! the first link is this pdf, it’s a version of the paper from April 2014 but that should be good enough.

How to read a research paper

But now the real work begins. I go into the paper and look for their comparisons: treatment group minus control group, controlling for pre-treatment information. Where to look? I cruise over to the Results section, that would be section 4.1, “Empirical strategy: direct effects,” which begins, “We first examine direct effects on individuals from the experiment.” It looks like I’m interested in model (4.3), and it appears that the results appear in table 6 through 12. And here’s the real punchline:

Overall, despite a relatively soft intervention – a one-hour documentary screening – we find clear evidence of behavioural changes six months after treatment. These results are also in line with our analysis of which components of the aspirations index are affected by treatment.

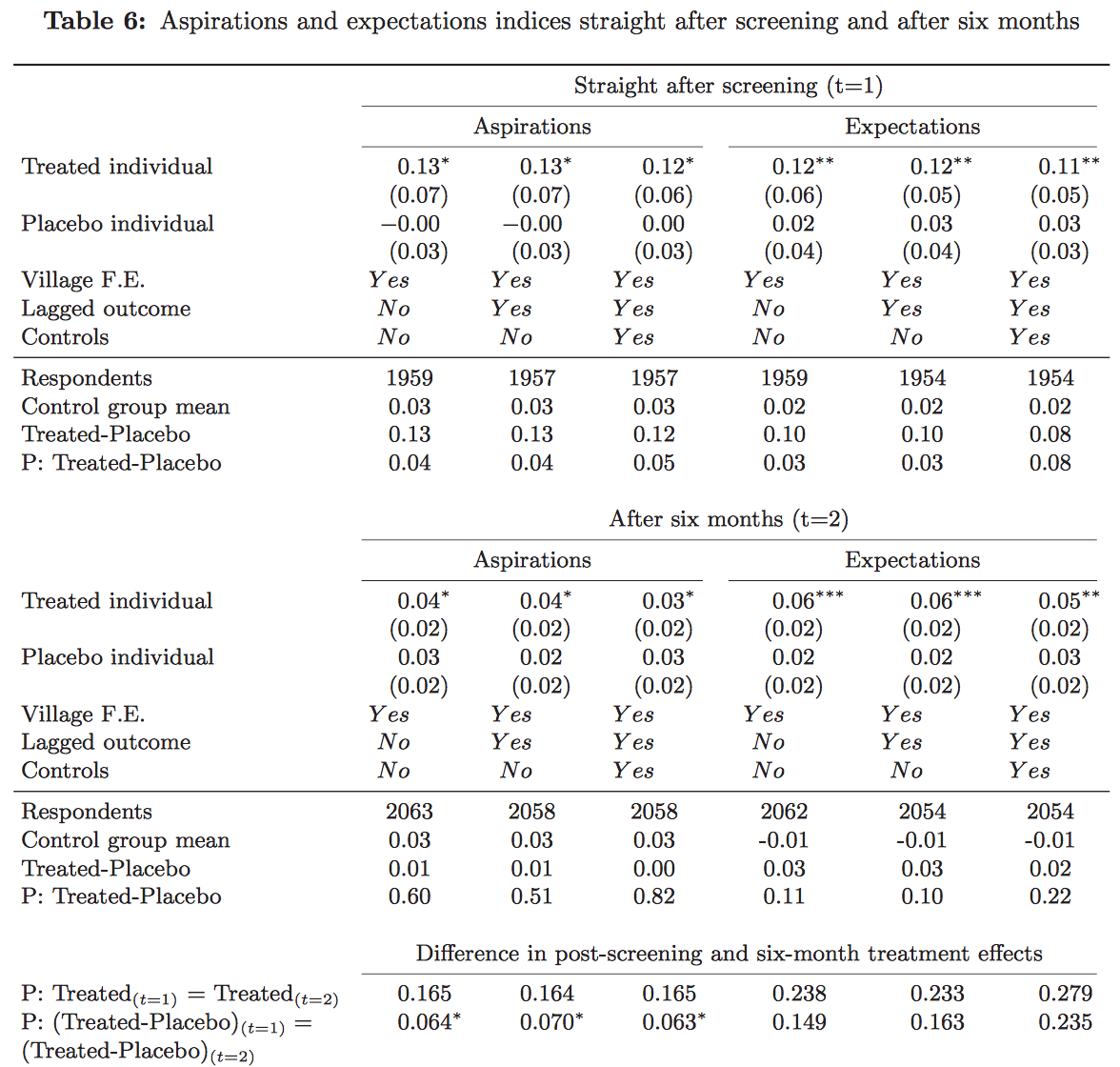

OK, so let’s take a look at tables 6-12. We’ll start with table 6:

I’ll focus on the third and sixth columns of numbers, as this is where they are controlling for pre-treatment predictors. And for now I’ll look separately at outcomes straight after screening and after six months. And it looks like I’m suppose to take the difference between treatment and placebo groups. But then there’s a problem: of the four results presented (aspirations and expectations, immediate and after 6 months), only one is statistically significant, and that only at p=.05. So now I’m wondering whassup.

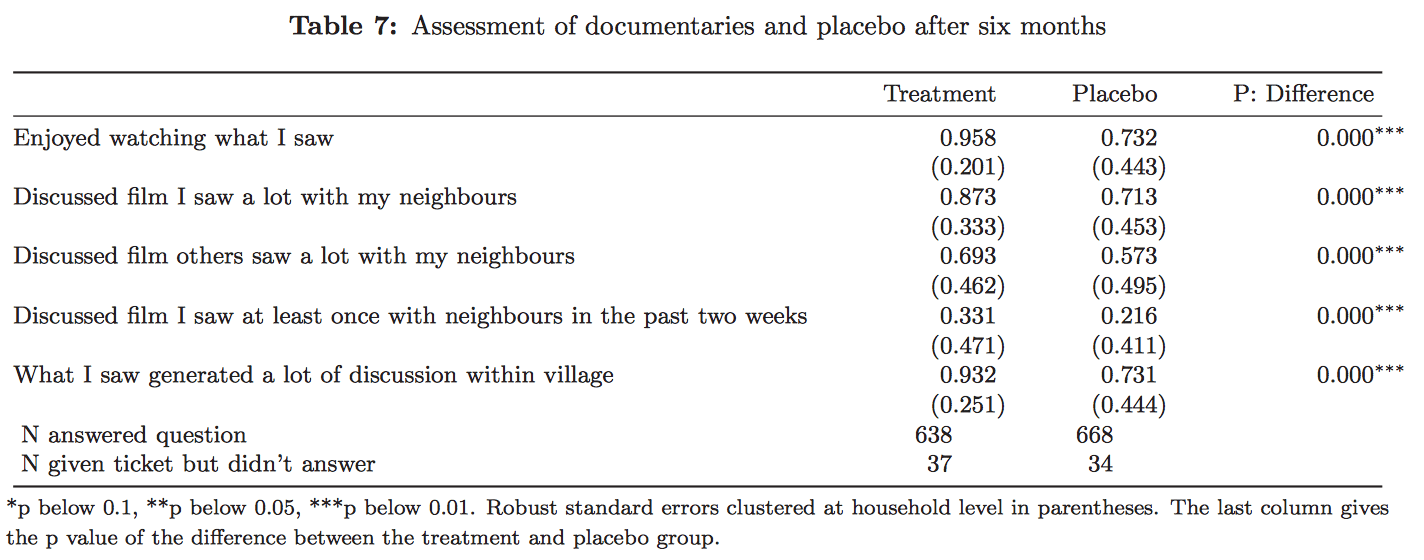

Table 7 considers the participants’ assessment of the films. I don’t care so much about this but I’ll take a quick look:

Huh? Given the sizes of the standard errors, I don’t understand how these comparisons can be statistically significant. Maybe there was some transcription error? 0.201 should’ve been 0.0201, etc?

Tables 8 and 10, nothing’s statistically significant. This of course does not mean that nothing’s there, it just tells us that the noise is large compared to any signal. No surprise, perhaps, as there’s lots of variation in these survey responses.

Table 9, I’ll ignore, as it’s oriented 90 degrees off and it’s hard to read, also it’s a bunch of estimates of interactions. And given that I don’t really see much going on in the main effects, it’s hard for me to believe there will be much evidence for interactions.

Table 11 is also rotated 90 degrees, also it’s about a “hypothetical demand for credit.” Could be important but I’m not gonna knock myself out trying to read a bunch of tiny numbers (868.15, 1245.80, etc.) Quick scan: three comparisons, one is statistically significant.

And Table 12, nothing statistically significant here either.

At this point I’m desperate for a graph but there’s not much here to quench my thirst in that regard. Just a few cumulative distributions of some survey responses at baseline. Nothing wrong with that but it doesn’t really address the main questions.

So where are we? I just don’t see the evidence for the big claims, actually I don’t even see the evidence for the little claims in the paper. Again, I’m not saying the claims are wrong or even that they have not been demonstrated, I just couldn’t find the relevant information in a quick read.

How to write a research paper

Now let’s flip it around. Given my thought process as described above, how would you write an article so I could more directly get to the point?

You’d want to focus on the path leading from your data and assumptions to your key empirical claims. What would really help would be a graph—“Figure 1” of the paper, or possibly “Figure 2” showing the data and the fitted model, maybe it would be a scatterplot where each dot represents a person, with two different colors representing treated and control groups, plotting outcome vs. a pre-treatment summary, with fitted regression lines overlain.

It shouldn’t take forensics to find the basis for the article’s key claim. And the claims themselves should be presented crisply.

Consider two approaches to writing an article. Both are legitimate:

1. There is a single key finding, a headline result, with everything else being a modification or elaboration of it.

2. There are many little findings, we’re seeing a broad spectrum of results.

Either of these can work, indeed my collaborators and I have published papers of both types.

But I think it’s a good idea to make it clear, right away, where your paper is heading. If it’s the first sort of paper, please state clearly what is the key finding and what is the evidence for it. If it’s the second sort of paper, I’d suggest laying out all the results (positive and negative) in some sort of grid so they can all be visible at once. Otherwise, as a reader, I struggle through the exposition, trying to figure out which results are the most important and what to focus on.

That sort of organization can help the reader and is also relevant when considering questions of multiple comparisons.

Beyond this, it would be helpful to make it clear what you don’t yet know. Not just: The comparison is statistically significant in setting A but not in setting B (or “aspirations had improved among treated individuals and did not change in the placebo or control groups”), but a more direct statement about where are the key remaining uncertainties.

In using the Tanguy et al. paper as an opening to talk about how to read and write research articles, I’m not at all trying to say that it’s a particularly bad example; it’s just an example that was at hand. And, in any case, the authors’ primary goal is not to communicate to me. If their style satisfies their aim of communicating to economists and development specialists, that’s what’s most important. They, and other readers, will I hope take my advice here in more general terms, as serving the goals of statistical communication.

My role in all this

A couple months ago I got into a dispute with political scientist Larry Bartels, who expressed annoyance that I expressed skepticism about a claim he’d made (“Fleeting exposure to ‘irrelevant stimuli’ powerfully shapes our assessments of policy arguments”), without having fully read the research reports upon which his claim was based. In my response, I argued that it was fully appropriate for me to express skepticism based on partial information; or, to put it another way, that my skepticism based on partial information was as valid as his dramatic positive statements (“Here’s how a cartoon smiley face punched a big hole in democratic theory”) which themselves were only based on partial information.

That said, Bartels had a point, which is that a casual reader of a blog post might just take away the skepticism without the nuance. So let me repeat that I have not investigated this Tanguy et al. article in detail, indeed the comments above represent my entire experience of it.

To put it another way, the purpose of this post is not to present a careful investigation into claims about the effect of watching a movie about rural economic development; rather, this is all about the experience of reading a research article and, by implications, suggestions of how to write such an article to make it more accessible to critical readers.

In the meantime, if any reader wants to supply further information to clarify this particular example, feel free. If there’s something important that I’ve missed, I’d like to know; also if anything it would make my argument even stronger, buy demonstrating the difficulties I’ve had in reading a research paper.

P.S. From a few years back, here’s some other advice on writing research articles.

Having also not read the paper, I wonder if the values in parentheses in Table 7 are sample standard deviations rather than estimated standard errors?

Pbaylis:

I was wondering that too. But the note at the bottom of Figure 7 explicitly says, “Robust standard errors clustered at household level in parentheses.” So I assumed that they’re standard errors. But I guess you’re right, it could’ve been an error in the compilation of the table, or it could be that the person who wrote the note at the bottom of the table is not the same as the person who computed the numbers.

Maybe they used non-robust standard errors to calculate the p values?

Elin:

No, I think Pbaylis and Russ are correct, that someone simply computed sqrt(p*(1-p)) and then put this in parentheses, mistakenly thinking it was the standard error. Just the old, old story of someone using the wrong formula. I am guessing that person A wrote the caption and person B filled in the table, and there was a lack of communication. Given that I was not able to figure out what was going on in the paper, perhaps it’s no surprise that the authors had some confusion too.

Did you notice that the sample sizes for the follow up are larger than for the initial measurement? And then Table 7 samples are totally different.

Andrew:

I think your approach is entirely appropriate. Indeed, the goal should be to write the paper so a skeptical reader can find convincing answers quickly. Of course, this is easier said than done. Simplicity and clarity are fine arts.

One approach is to start with the findings, in Figure 1 Section 1, and then explain how we got there. Unfortunately, and I am guilty as charged, most papers start with the road to the finding; postpone the finding to Section 4 or 5; and bury it in a whole bunch of tables to satisfy reviewers.

So in terms of the writing advice you mention in your P.S., I would say that instead of starting with the conclusions and then working back, I would start with Section 1 on findings and then work forward. Same thing really, but more logical if the goal is to convince skeptics on a quick read. That is, my proposed structure is:

1. Intro (Exec summary: Research question, why important, what we find, how we find it)

2. Findings

3. Materials and methods

4. Threats to inference / ancillary analyses (some in annex)

5. Conclusion (How findings advance what we think we know, with reference to literature).

The current standard:

1. Intro

2. Lit review

3. Methods

4. Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Andrew,

I agree that the evidence here is only suggestive* and that the idea that a 1 hour documentary would change long-term behavior in majorly important ways is something of a stretch (although – Kony, right?, which at least changed some sorority girls’ Facebook behavior for a while).

That said, if I were to guess as to why people in my field think this is so important**: We know that peer effects matter and we know that adult earnings and occupational/educational choices are partially (maybe even strongly) determined by our parents. And I think some of us have thought, abstractly and informally, that there is some element of a “choice set” at work in people’s decisions about their profession. And part of that choice set is just the set of options you can conceive of.

An example from my life: I was working a job I hated. I started asking everyone I knew if they knew of any job openings. One colleague says to me “I work at the soccer channel on the weekend.” To which I said “There is a soccer channel?” It had never in my life occurred to me that there are hundreds of people who sit in front of machines and press buttons to make soccer show on your TV screen, and that much of this work involves…watching soccer! The choice of being “TV broadcast engineer for soccer channel” was not in my choice set before I talked to that guy, and so I couldn’t aspire to do that (but then I did start aspiring, and then I did that job for a few years, and it was awesome).

So I would guess that, wandering around rural Bangladesh or Guatemala or wherever, we’ve all looked at kids playing with a tire in the street and thought “these kids don’t even know that there is a world out there in which they could make all these other choices about their future”. We just weren’t imaginative enough to come up with ways of testing the theory that weren’t, say, mess with 20 undergraduates in a lab**. And this seems like a totally reasonable first-pass attempt at getting at this feeling that a “potential career choice set” is a big obstacle faced by poor children in rural areas***.

*I think the p-values (aside from all epistemological p-value criticism on this blog) are too small – the standard would be to cluster SEs at the level of randomization, but there are too few clusters, so they cluster at the household level which is likely insufficiently flexible/robust. I would, were I to referee this, suggest both wild cluster-t bootstraps and (forgive me) randomization tests for these p-values.

**Maybe this is the Development equivalent of messing with 20 (ok, 18!) undergrads, but as a kind of pilot for an idea, I might be OK with that. Plus they would be 18 low-variance subjects (because each “subject” is a whole village of people).

***I actually have no idea whether lots of other people have had this thought, but it seems like a natural reaction, in that it happens to me all the time, which is obviously a totally objective measure of “natural”. It also feels “in the air” to me, given our recent interest in decision making behavior and subjective valuation, etc. – things where people’s subjective beliefs play a prominent role. Merge that with choice theory and you’ve got, well, a “future things I could conceive of doing with my life choice set”.

“this feeling that a “potential career choice set” is a big obstacle faced by poor children in rural areas”

Yes, I think this feeling is quite plausible.

For example, when I was graduating from college in 1980 and interviewing for a job, I didn’t lack for ambition or self-confidence, like a lot of poor peasants suffer from. Still, I had a hard time being convincing in interviews because I didn’t really have a picture in my head of what you did all day in any particular job, and I’m not good at faking things.

So, I went to MBA school, which is kind of a Let’s Pretend experience for trying out different careers, and by 1982 I was far better in interviews because I had done the kind of projects you would have to do in the various jobs I interviewed for. (Unfortunately, they don’t let 21-year-olds go to B-School anymore).

Whether watching a 1 hour documentary is enough is a different question, however. But in theory I think it’s extremely plausible that your society gives you signals about what kinds of careers are plausible. For example, I witnessed attitudes about women’s careers change with extreme rapidity from, say, 1969-1974. (Not much has changed in the 40 years since then, of course.)

Good article, but I agree entirely with Fernando’s comment. As a busy policy maker looking for evidence base in research, I want to know what the findings were (or weren’t) immediately. If that suits my need, then I’ll look to the methodology to satisfy myself of the reliability of the evidence. That ‘reverse pyramid’ approach is how a reporter would write up the research.

Richard:

I think what you and Fernando call “findings” is what I am calling “conclusions.” And what you are calling “conclusions” is what I would call “speculations.” That is, I think we’re in agreement: the author should put his or her findings up front, then give the evidence for the claims, etc. One of my difficulties with the paper under discussion above is that (a) it’s not quite clear what they claim are their key findings, and (b) I can’t really see all their findings in one place.

IMHO the paper should be written with a mind toward a reader who wants to read it slowly and take in as much detail as possible. It is true that many (majority?) of readers don’t care about slow reading and want results first. But they will read the paper in any odd order they want anyways, looking for supporting information and explanations wherever needed. No point in trying to present information up front for such readers. If sec. 5 is where the results are, a willing reader will turn to section 5 ignoring previous 4. Some years ago I was taught that a typical experienced reader reads in the order abstract-conclusion-results, with a possibility of lost interest at any stage. If you clearly mark this sections, it does not matter in which order they are put.

Without looking at the paper but only your description, I guess that the numbers in parentheses in Table 7, which you assumed were SEs, are merely \sqrt {p(1-p)}, where p is the number not in parentheses. This is pretty common to include, even though it does not add any new information for a table of percentages. I know one author who recommends against such decorations.

Russ:

See my response to Pbalyis in column above.

Hi, Andrew.

There was some problem with comments displaying. I didn’t realize I was not the first to comment.

Anyway, it is easy to check that what I said is right, though I did not check all of them.

–Russ

Russ:

Yeah, it’s too bad they botched that; maybe some sort of flaw in the division of labor. On the plus side, it’s no “Reinhart and Rogoff” as this all happened at the pre-publication stage.

Let’s just hope that people catch the larger message that their papers should be more clear.

I agree with most of what’s been said about the organization of the paper. And the results (after six months) are on their face very weak, hard to see why the authors (much less Blattman) would crow about them.

But, beyond that, the design of the experiment asks us to swallow a lot: the authors provide a nice review of evidence that aspirations would affect behavior (pp. 4-6), and let’s say that’s true in general. But then their intervention (an inspirational film) could just as well (i) introduce an error into the measurement of aspiration and/or (ii) change the relationship between aspiration and behavior for the treated individuals (I think Leamer would call these additive and multiplicative confounders, respectively).

To put this another way, jrc testifies to a personal case where a small bit of information changed both aspiration and behavior, which is in keeping with the Bernard et al story; on the other hand, I can come out of a movie with my aspiration to be James Bond or Gandalf greatly enhanced and though I might, heaven forfend, reveal this to somebody (even to a researcher) it is unlikely to change my behavior. Call these the motivational effect and the Walter Mitty effect. I don’t see that Bernard et al have any way of distinguishing between them because (in common with so many psychological researchers) they aren’t measuring behavior.

Pingback: Shared Stories from This Week: Dec 05, 2014

Pingback: When the evidence is unclear - Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science

Pingback: How to read (in quantitative social science). And by implication, how to write. - Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science

The accumulated 60 years of Communication ‘effects research’ shows little to no impact on behaviour following ‘exposure’ to information. Time and time again, this strange view of human communication as something delimited to ‘messages’ which bring with them ‘effects’ continues.

The old, and unfunny joke (excerpted from a New Yorker cartoon), still holds: “when you consider the awesome power of television to educate, aren’t you happy it doesn’t?”

Many of the studies Andrew easily identifies as flawed appear to stem from this long running, and from my perspective, odd perspective about what human communication is, how it works, and how it might be productively studied. Himmicanes, air rage, power poses, etc are all based on the easily falsifiable cultural notion that ‘messages’ themselves carry with them causal force. They simply do not.

Human communication is a social accomplishment, a distributed activity engaged – not done – by persons (i.e. no individual ‘communicates’ – one engages communication).

As long as we hold onto the silly notions of messages carrying force, we’re going to see studies designed to show ‘direct effects’ which do not exist.

Quote from above: “Himmicanes, air rage, power poses, etc are all based on the easily falsifiable cultural notion that ‘messages’ themselves carry with them causal force. They simply do not.”

Perhaps if you repeat someting long enough, (at least some) people will (start to) believe it.

In light of all these “silly” studies that have gotten so much attention, and allocates resources, in the last 30 years or so i have wondered whether these studies are some sort of way to get a message across. You gotta put on your tin foil hat though to go along for the ride, at least to some extent. Here we go:

To me a lot of these “silly” studies a lot of the time involve conclusions that basically fall into a few categories like “people are influenced by little things”, “people do things due to unconsious reasons that they are not even aware of”, “people are ‘social animals’ and think in ‘groups'”, etc. These to me seem conclusions that would fit nicely with viewing, and or wanting to turn, people into what i believe the hip kids call “sheeple”.

What if governments or industries or big corporations could give certain researchers and topics lots of money, and attention, to try and get a point across to the general public or policy folks. Social studies could then repeatedly “investigate” and “conclude” certain things, based on certain studies, that then subsequently get talked about in the media. If this happens for decades, and the (core of the) message and conclusion is similar, you could have people starting to believe things. At least some people.

Basically the conclusion, and perhaps even the (small?) set of topics and hypotheses, of social science studies are then communicated, and used, to in turn communicate something that some people want to communicate. Perhaps social science studies, and the media, are the “materials” and the “manipulation” of a giant experiment where the general public are the “participants”.

I’m taking off my tin foil hat now.

Quote from above: “In light of all these “silly” studies that have gotten so much attention, and allocates resources, in the last 30 years or so i have wondered whether these studies are some sort of way to get a message across. You gotta put on your tin foil hat though to go along for the ride, at least to some extent.”

You can also possibly not put on a tin foil hat, and simply view this as a possible process that can come to exist without any conscious action.

If you have things like:

# people that (partly) decide who and what to give grants to, and who and what to publish

# “friendly” colleagues who work together to promote, cite, review, etc. eachother’s work

# universities who want their researchers to also teach

# teachers can teach their “own” papers and topics

# researchers can hire PhD students to basically do the work the researcher thought about and are working on

i reason that you could end up with a very small set of topics and researchers that (for a period in time) basically decide a large part of allocated funding, attention, etc.

It’s part of why i think grants should be handed out evenly amongst researchers (e.g. without deciding what they should investigate), why i think PhD students should not perform their professsor’s work (e.g. they should come up with their own ideas), why i think the traditional editor-journal-reviewer model of scienctific publishing should be stopped, why i think the media should not report on scientific findings, etc.

UBI for University Basic Income!

When you got PhD, government should provide you with some basic money for researching whatever you want.

“When you got PhD, government should provide you with some basic money for researching whatever you want.”

Over here in the Netherlands PhD students get a basic income if i am not mistaken, that doesn’t solve the possible problematic issue i was pondering.

I reason the possible problem lies a step before that: i get the idea that at least in psychology PhD students apply for topics and projects that their advisor (i.c. a professor) came up with.

This possibly helps set in motion a possible (endless?) cycle of similar topics and researchers getting a large part of funding, attention, resources, etc. And i think it might also contribute to the possible “skewed” and “weird” (power-) relationship between professor and student which may have caused many problematic issues in academia.

That’s where i think a part of the problems in academia may stem from as i conjectured above.

This discussion reminds me of something I read earlier today (Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, July 2019, p. 518)”

“In the 19th century and beyond it was widely rumored that there were two ways a young man could find a good position as a mathematician: publish, publish, publish, or marry the daughter of a senior mathematician. Picard married one of the daughters of Charles Hermite.”

“i think grants should be handed out evenly amongst researchers (e.g. without deciding what they should investigate”

When the grant reviewing process works as it ideally should, its purpose is to assess all information available to make a decision whether not to award the grant to the proposer — with the understanding that it might or might not be spent entirely on the exact research program proposed. For example, I once got a grant review that said something like, “The problem proposed in the grant is a very difficult one, and is not likely to be solved in the time covered by the grant. However, it is a question well worth studying, and based on the proposal and the applicant’s previous work, it is very likely that she will come up with some worthwhile results that make progress toward ultimate solution of the problem and/or give important insight about related problems, so I recommend awarding the grant. “

“When the grant reviewing process works as it ideally should, its purpose is to assess all information available to make a decision whether not to award the grant to the proposer — with the understanding that it might or might not be spent entirely on the exact research program proposed.”

I don’t even think that would be optimal. Regardles of exactly how the money gets spent, and on what topic or hypothesis or whatever, i reason the grant reviewing process might be similar to the paper reviewing process. I am not a fan of the paper reviewing process, and i reason it may have contributed a lot to the current poor state of science/academia.

Just like i think the traditional peer reviewing makes little sense, so do i think grant reviewing makes little sense. I reason similar problems can occur in grant reviewing as in paper reviewing. To name a few possiblities:

# incompetent people reviewing and awarding grants (?)

# “friends” reviewing and giving eachother grants (?)

# researchers asking for way too much grant money because that’ll get them some “rewards” from their institutions (?)

# researchers being rewarded by how much grant money they gathered (?)

I heard one time that Meehl only received one grant in his entire career. I don’t know if that’s correct, but i hope it is because i feel that that would just about be how it should be (for several reason that i can’t even explain)

I wonder what would happen if you 1) spread grant money equally amongst resarchers, and 2) don’t let universities take a piece of the grant money for “reasons” (if that is indeed what happens currently).

I reason that could lead to several processes that would lead to possibly improving science. I reason that could lead to researchers possibly deciding how to optimally, and responsibly, use the grant money. They could decide to work together and put the money of each individual researcher together to spend when deemed useful. And crucially concerning this all, i reason they would not waste money because there would be no reason to (e.g. they would not be “rewarded” by their institutions because these institutions don’t receive a piece of the grant money their staff receives).

Every researcher would also have the opportunity to “do their own thing”, which in some cases could lead to truly innovative and revolutionary work by some genius, but i reason it may also encourage some more thoughtfull actions concerning how, and why to spend money on certain topics, and studies. Overall, i reason it could also aid in a selection and evolution process of making sure the best and brightest minds are in science/academia (and not for instance the people who get the most grant money, or most media attentions).

One possible problem i can see is that distributing money could lead to each researcher receving so little money that they can’t do anything with it. However, i don’t think this is (largely) true. I know most about psychology, and i reason from that viewpoint mostly. If i do that, i think big parts of grant money received in Psychology 1) gets wasted on paying (too many) PhD students to do the work the professor should be doing, 2) gets wasted on “flimsy” effects and “theories”, and 3) possibly gets wasted by being “directed” to the institution for “reasons” (but i am still not sure if, and how much, this happens).

Should there actually be too little money in some cases, i reason people who think that can simply join forces with their money if they think it’s worthwhile. Additionally, i think this process could help to (finally!) test and compare theories and finding out which variables, processes, and phenomena are most useful in explaining and understanding behaviour. This may not only be in line with scientific principles, but may in fact also save resources because you wouldn’t be wasting tons of participants on “small effects”, and you wouldn’t be wasting tons of resources on “flimsy effects”, etc.

Regardless of whether the above ideas make any sense, i am increasingly more puzzled and disappointed to almost never hear anybody speak or write about what i think might be the core of problematic issues in academia: money, power, and influence.

None of the recent proposals to “improve” matters seem to me to mention any of this, let alone take this into account when thinking about how to properly do science. To me it’s almost like these things are either 1) taken for granted and viewed as unchangeable, or 2) being kept under the wraps.

For me it is therefore also no surprise to think that many of the recent proposals to “improve” things will possibly only reinforce and replicate many problematic issues and processes.

An exception to this for me has been the following paper/chapter, which i would therefore also like to mention and link to here: “Excellence by nonsense: The competition for publications in modern science” by M. Binswanger (2014)

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-00026-8_3

Anonymous,

do you have any practical advices for low-power players in this game?

Like, if someone is a recently graduated PhD, what would you recommend them to do? Don’t partake in Academia and search alternative funding?

Quote from above: “do you have any practical advices for low-power players in this game?

Like, if someone is a recently graduated PhD, what would you recommend them to do? Don’t partake in Academia and search alternative funding”

I don’t like giving advise to other people. I don’t even think i am “managing” my own life optimally, let alone be able to hand out advise to others how to live theirs. I want people to do “their own unique thing” and think about things and be responsible for their own choices and actions. I do think that sharing ideas, thoughts, and providing information and stuff like that might be in line with those things, which is why i think i like to just stick to doing that.

I can tell you that i am really glad i never got hired for the few PhD positions i applied for. I can tell you that i myself don’t want to participate in academia anymore. I can tell you that i myself don’t want to ask other people for money. I don’t want to publish in “official” journals anymore. I don’t even want to write papers and publish them in “non-official” places anymore.

And i can tell you that i am glad blogs like this one exist, where i can discuss matters, try and offer my perspective on things, share my thoughts and ideas, and read things from other people that i think might all be important in (improving) science/academia.

Perhaps in doing this all, i am optimally doing what i want to, and perhaps could, do. Perhaps that’s all i want and need.

Anonymous said,

“i think big parts of grant money received in Psychology 1) gets wasted on paying (too many) PhD students to do the work the professor should be doing, 2) gets wasted on “flimsy” effects and “theories”,”

I don’t know just what the situation is in psychology, but I know that in many fields (e.g.,engineering) one of the main purposes of writing grant proposals is to try to obtain support for graduate students.

Quote from above: “I don’t know just what the situation is in psychology, but I know that in many fields (e.g.,engineering) one of the main purposes of writing grant proposals is to try to obtain support for graduate students.”

I think that’s similar in Psycholgy as well, at least in the Netherlands i think (which is what i alluded to with my comment).

Now to me this is insane: there are way too many PhD students as it is, and i think it’s not fair to waste money on “educating” even more. Nor do i think it’s fair to ask for money for a project or research question when it actually is about asking money to pay some PhD student to do the work the professor should be doing.

Also see the book by social psychology fraudster Diederik Stapel, who on page 5 wrote the following https://errorstatistics.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/fakingscience-20141214.pdf:

“Doctoral dissertations are an important source of funding for Dutch public universities. So the more PhD students who graduate, the better. For every successful dissertation, the government hands over a little more than $100,000. Naturally, this leads to some creative ideas for ways to increase the numbers of doctorates being awarded.”

Again money (power, and influence) may lie at the core of many problematic issues in academia/science. If this is correct, why aren’t all these “let’s improve science” folks talking about those things i wonder?

Quote from above: “If this is correct, why aren’t all these “let’s improve science” folks talking about those things i wonder?”

I think it’s because they might be too busy asking for even more money for their “let’s improve science” projects, which of course will be caried out by young folks again. It seems to me that they got money to mess things up, ask for money to try and fix it, and then come up with idea that cost a lot of money again!

Anyway, i came up with some ideas that (almost) doesn’t cost anything extra, tries to combine, and alter, some stuff that currently happens in a minimal fashion so that things can hopefully improve, tries to (set up to) tackle the money, power, influence thing, and will possbly (help) improve matters from a more dispersed and hopefully scientifically sound and responsible perspective. E.g. see here for one of those ideas:

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2017/12/17/stranger-than-fiction/#comment-628652

“Poor people often do not make investments, even when returns are high.”

Reminds me of the “Learned Helpessness” experiments by Seligman.

Psychological illness is difficult.

When I was in ******* last summer, I sincerely believed that when I would enter my home country, I would be taken into custody by FBI and then arrested for things I had done in the past. This thought persisted for a few weeks, and kept me from sleeping, may be 1-2 hours a night. Having heart palpitations, panic attacks, cold sweats, etc. It was a psychotic delusion from Mania.

Even if someone has excellent critical thinking skills and knows that these thoughts are delusional, and you can rationalize, these thoughts don’t go away. People not well versed in mental illness look at it as irresponsibility, immaturity, etc. No medication makes it go away, they only help manage the symptoms.

Nothing happened, customs let me walk through with no issues. It was a delusion.

“Poor people often do not make investments, even when returns are high. ”

What definition of “poor” is being used here? When I think of “poor people”, I think of people who don’t have time or money to invest — they may be working at two jobs to pay for the basics for themselves and their families (food, a place to sleep, transportation to and from jobs .. . hoping and praying that no one gets sick or injured).

These are good points, but also remember that to an economist an investment is anything you spend money on now to receive benefits in the future. So buying a 12 pack of toilet paper instead of 1 roll at the local gas station is an investment.

still, poor people often understand exactly how hard that can be better than economists in armchairs. transaction costs are usually underestimated by a lot (for example how long does it take to get to the store that sells the bulk packs?)

anyway I think there is plenty of room for improving financial and economic knowledge and thereby improving outcomes. but we need to be realistic about it.