Piotr Mitros wrote to Deb and me:

I read, with pleasure, your article about the impossibility of biasing a coin. I’m curious as to whether researchers believe what they write. Would you be willing to place some form of iterated bet?

For example: I provide a two-sided coin and a table. The table looks like a normal table, and the coin looks like a normal coin (although most likely, someone handling the coin will be able to tell it is doctored — if this is a problem, we could probably even do away with this requirement).

The coin is tossed into the air, a large distance, allowed to spin many times, and lands. You were concerned about fairness of the toss. You are welcome to hire an undergrad or similar to do the tossing, assuming you provide unbiased instructions. Heads, I collect $99. Tails, you collect $101. If the coin is fair — as your article claims it has to be — the expected outcome is you make a buck on each toss. It is a random process, so we can keep going for e.g. 40,000 flips — which should give you confidence of coming out ahead, again, assuming you believe your article. It is also about $2000 at undergrad income assuming 10 seconds per flip.

We both do our best to act in good faith. In other words, we don’t e.g. miscount flips, give bad instructions, welch [hey, that’s a racial slur!—ed.], swap coins, etc. The bet is on whether coins can, indeed, be biased.

I replied:

The problem is that the outcome can depend on how the coin is flipped, conditional on the initial state of the coin (i.e., which side is facing up when it is flipped). I have no doubt that a person can flip it to make it more likely to come up one side or the other, but then the bias is a property of the flip, not the coin.

Piotr:

In the proposed protocol, I offered to have you hire the person doing the flipping, and give them clear, good-faith instructions on how to make the flip maximally unbiased. I assume this would mean you would alternate starting side to remove bias for initial state, toss high up into the air, and spin quickly around the appropriate axis.

Me:

Yes, in this case I think the probability is .5 and so I don’t think it would make sense for you to offer $101 for tails and $99 for heads, as this bet would have negative expectation.

Piotr:

I appreciate your advice and concern. As a statistician, you are surely aware that humans are not rational economic agents; I may have any of a range of motives.

If you believe what you just said (and your paper), you should also believe that the experiment overall has a $40,000 expected income for you, and that furthermore, the number of flips is sufficient that it would earn you money with pretty good confidence. Indeed, the odds of any large losses should be exceeding small. So you should accept the offer.

Me:

Hi, don’t take this personally, but I’m not in the habit of trying to take $40,000 on a bet from someone I don’t know!

Piotr:

It’s not a bad habit. You’re likely to lose more money than you are to make money.

If it would help:

I’m confident I could find a number of mutual acquaintances who would be glad to make an introduction and vouch for my character. We are in similar enough circles that I am sure we have many colleagues in common.

Furthermore, I’d be glad to place some funds in a credible escrow service, so you could be confident of pay-out, and have this managed by a credible, independent third party.

If I were to come out ahead, I’d be glad to earmark the money for a good cause. I would be glad to place the money there, so I would not personally benefit either way.

In other words, I am glad to take every action needed for you to have complete confidence in the validity of the bet. Furthermore, I am a sufficiently public figure that if I were to engage in anything unfair (beyond providing a biased coin, which I am completely open about) the cost to my reputation would be much greater than $40,000.

If you do decline, I would appreciate a better excuse, however!

Me:

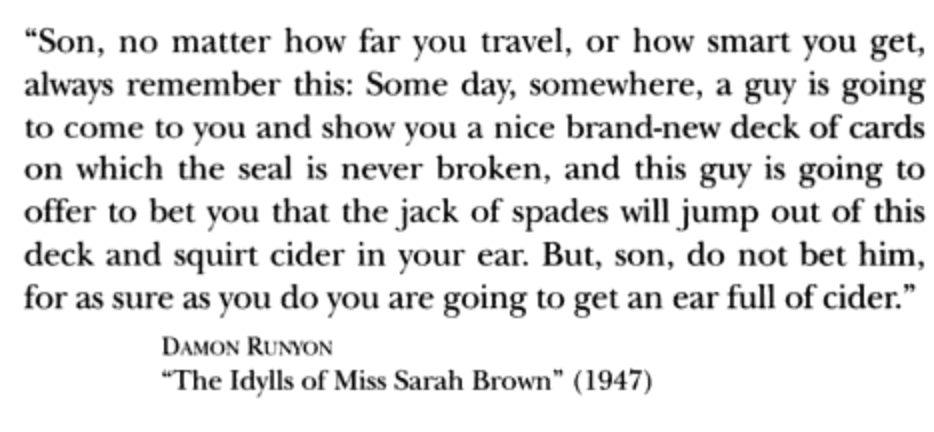

There is this famous passage which pretty much sums up my attitude:

Piotr:

By the way, as you can imagine, my expectation was that you would not take the bet (however, if you had, I would have found a way to make good on the offer). I was hunting for something juicy to toss into a followup article.

All good, then.

Why does Piotr describe that a table is needed? Your abstract says right out that the coin should be caught?

welch [hey, that’s a racial slur!—ed.]

But not in the United States; the linguistic connection between welch and the Welch is nonexistent. In fact, of all the ethnic, geographical immigrants I would say that the Welch have a low or indeed, no profile.

In the UK, the nationality is usually referred to as Welsh and not Welch.

The linguistic connection to the verb “to welch” meaning to renege on a bet may go back hundreds of years and the similarity to “welsh” may have come from insinuated “welsh” inferiority. That of course might just be my “english” on the subject :) http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/English?q=english

Wow—that’s great. The labeling of “welch” as a racial slur may itself be a racial slur! How recursive is that??

There’s a Piotr Mitros with bio info on the website http://mitros.org/p/

Given that bio, if he is the one making the offer, I would pass on the bet. He can probably easily cover the $40 K though. It seems highly likely that Mitros and Gelman have mutual friends or at least connections with two intermediate individuals.

Here are some quotes from the bio that indicate to me that he is the kind of person who could build a biased coin:

. . . designed the analog hardware — from blank slate all the way through human trials — as well as some work on numerical algorithms and other areas of the system.

. . . Working for Talking Lights, I designed and built an instrumentation photodetector, where the noise was dominated by the shot noise in the photodetector diode (caused by discretization from individual photons striking the sensor). It had several MHz bandwidth. It was designed to measure very small signals on top of a large constant light source.

[undergraduate work] . . . In Roberge’s Advanced Circuit Techniques, I designed a high speed line driver. It was a one-shot design (components were chosen to match each other, and it would not work with randomly chosen parts), but it had a small signal bandwidth of 60-70MHz, on a protoboard (about 5x the speed of the fastest project people were aware of from current and past semesters, and if I recall correctly, 30x faster than spec). This was small signal; for large signals, it slew-rate limited well before (although the slew rate was still very, very significantly above spec). Writeup was painfully bad, due to time limitations.

Wonderful stuff! This blog post reads like a Roald Dahl story (only less gruesome):

http://www.classicshorts.com/stories/south.html

Andrew: Haven’t you written that hypothesis tests are uninteresting because the null is measure 0? How does that jive with the claim a coin is unbiased.

All coins are almost surely biased, and claims to the contrary are likely based on sample sizes too small to detect the bias.

Dan:

We discuss all this in our article.

Odd. I just read the article for the 2nd time, and I’ve been unable to find this both times.

“At any rate of spin, it spends half the time with heads facing up and half the time with heads facing down, so when it lands, the two sides are equally likely (with minor corrections due to the nonzero thickness of the edge of the coin) . . .”

When we say fair, we mean “close to 1/2.” But this point was so obvious to us that we did not bother to emphasize it.

“allowed to spin many times”

This is the trick. A flipped coin is basically “fair” (though the flipper can make the flipping biased), but a spinning coin is biased towards landing heavier side down.

As always, Paul Samuelson provides the correct response to this offer! https://www.casact.org/pubs/forum/94sforum/94sf049.pdf

Wow. This is so on-point it’s uncanny.

What a perfect Bayesian example. Your prior on a coin is Pr(heads)=.5 But the unexpected offer of a wager on that proposition is new information which had to be incorporated to create a new posterior, one in which Pr(heads) considerably greater than .5. And the incorporation follows the Lardner Corollary to Bayes’ Law.

I of course meant Runyon, not Lardner.

I think it’s clear your correspondent has something in mind other than changing only the density of the coin (considered as a spatial function, I mean). The theorems of rigid mechanics that give rise to the no-bias claim don’t consider electric or magnetic forces…

This reminds me of “The $5000 compression challenge”, which is a pretty good story: http://www.patrickcraig.co.uk/other/compression.php

It’s long, but the short version is:

* Someone tried to create an impossible contest involving file compression

* The author found a loophole and asked for $5000 when he “won” the bet.

* The creator of the contest was not pleased and eventually threatened legal action

I think you made the right decision, Andrew. Although I would still like to see what Piotr came up with!

Andrew,

There is certainly some value in learning what Piotr’s “trick” is.

Would it be possible to use this invitation as an “opening” to negotiate stakes that would allow you to learn the “trick” for a cost that is worth it to you?

Since a lot of us would like to learn the “trick”, perhaps you can start a kickstarter?

JD

David:

That’s an entertaining story. But I didn’t see the part where the creator threatened legal action.

“If you insist on pressing your request for $5,000 I shall be forced to defend against any such claim on the basis that you did not satisfy the requirements of the challenge, and, if necessary, for fraud.”

Provided that Piotr agrees also that the bias is inherent in the coin, and not in any external interaction with the coin, that is, if his bias could be achieved using any table in any room in the world without the use of external power sources, I’d be very very interested in how he plans to achieve this. If he’s just talking about an electromagnetic control system using a power source to exert torques on the coin… then yeah, I don’t think that counts as “a biased coin”.

I think that “electromagnetic control” is highly likely to be what underlies his system.

Recall the following:

(1) the table is part of the set up—apparently flipped coins are to land on the table.

(2) the bio of the Piotr Mitros that I found on the web shows experience in (a) vision processing, (b) medical imaging, and (c) high-speed analog drivers.

The table plus those skills suggest one possible design. The table contains sensors that monitor the orientation and position of the coin. Using that information a processor predicts whether it will land heads or tails. Assuming that the bet is heads, the processor does nothing if the projected outcome is heads. If the projected outcome is tails, then, as the coin nears the table, the processor energizes a electromagnet (solenoid coil) right under the point of predicted impact. The falling coin’s descent is slowed by the magnetic field but but the coin keeps on spinning. It is now more likely to land heads than before it was slowed down. The sensible design would probably have an array of small solenoids—not just one big solenoid. A big coil would create a field that might shake things in the room or cause things like keys in peoples pockets to vibrate a little.

A coin that was flipped fairly high, say four feet above the table, would cover the last six inches of its fall in about 0.03 seconds—so a magnetic pulse in the range of 10 to 30 msec would probably be all that could practically be used. Such a pulse would probably be hard to notice unless sprinkled some paper clips all over the table.

If one assumes that slowing down the falling coin gives the same outcome as a second, independent flip, then the odds of heads rise from 50% to 75%. For a given rotation rate, one could probably adjust the pulse duration to give a selected bias. Very weak pulse, 52% of heads. Strong pulse 55% or so?

See http://video.mit.edu/watch/physics-demo-lenzs-law-with-copper-pipe-10268/

One can imagine a variety of improvements to the above rough design. Most importantly, the processor could tailor the magnetic pulse to take into account the rotational speed of the coin.

Bob

Bob:

Cool! I don’t see why Piotr couldn’t just show me directly–that is, I don’t see the purpose of the whole betting thing–but it the setup you describe sounds fun.

Better video. More on point.

http://video.mit.edu/watch/ring-falling-in-a-magnetic-field-8291/

I have no idea what he had in mind, but really, this is trivially doable with simple permanent magnetism.

1) Buy a package of 2 latch magnets, for example 07220 from Master Magnetics. Each is about 1″ x 5/8″. $2-#3. My tiny local hardware store had them.

2) Slide the magnets loose from the steel casings.

3) Place magnets on top of each other, so they stick together, then mark each H(ead) and T(ail) on corresponding sides, so that H’s(T’s) repel.

3) Place one magnet under a piece of paper, H up.

4) Attempt to drop the other magnet so it lands T up on the other magnet. I’ve tried this from an inch up and it flips.

Try *placing* the other magnet T side up on top of the one underneath.

Ahh, but unfair, paper is thin, SO

5) Place first magnet H up, under paperback book, say 5/8″ thick. Try to place other magnet T side up above the first.

So, the bet:

a) Prepare table: glue a bunch of these magnets to the bottom of the surface, H side up.

b) Get an appropriate coin and magnetize it so H is the same oreintation as the magnets.

In the US, that’s the 1943 penny, but in checking my old foreign coin folders, in a few minutes I found a British penny, German 50pfennig piece, and Hong Kong 10cent and 50cent coins.

Coins won’t be as strong as these little magnets, but would good enough for bias.

c) Depending on the coverage density of glued magnets and the coin strength, I’d guess it’s possible to approach ~100% Heads, i.e., ~$99×40,000, or nearly $4M….

Why get complicated? For example:

a) magnetized steel cent, plus

b) ordinary magnets in table.

I’m not so sure about the coin bet, but I would definitely take the cider-in-the-ear bet. See if Piotr will offer me that one.

Gelman & Nolan are mainly concerned with weighting the coin, or altering it’s aerodynamics. What is the function relating angle of the coin when it is caught, to its final position (heads-up, heads-down) when it comes to rest. The model in Fig 3 of the paper assumes that the range [0-360) degrees is partitioned exactly equally into heads-up and heads-down basins.

But the mechanics of the coin’s interaction with the hand may be more complex than that. The mechanics of the coin’s interaction with a *table* will be not quite as complex, permitting it to be manipulated. Piotr specified a table, although Gelman & Nolan specified that the coin would be caught in the hand: this is perhaps significant.

When a fair coin strikes the table at a slight “heads” angle, it experiences a slight torque towards the tails side, and vice versa. Beveling the edge would selectively reduce this effect for one side of the coin, no? Maybe this is what Piotr intended.

One could also try manipulating the coin edge to give anisotropic friction with the table, but that seems less effective, and would certainly be more difficult.

+1 for the Runyon quote.

Indeed, I have always loved this quote. When I was young I was an amateur magician and this is one of the quotes that bubbled up when I was learning.

The sum of 40000 flips would typically end with a deviation between +-200 so between $-19800 and $20200 for a fair toss. Still a wide range even with that slight advantage.

Though the tosses that don’t advance the net sum would bias these by something like +$40000

It is not clear to me what you are calculating here.

This does smell fishy. However, here is a dose of devil’s advocate:

1. What if the Damon Runyon character had written a paper purporting to prove that the jack of spades can never squirt cider?

2. More generally, shouldn’t scientists be willing to put their money where their mouths are? Einstein was eager to test his predictions about relativity. The stakes in this case are really high, but if they were lower, why wouldn’t a scientist want to test his or her theory?

Jim:

Our paper is what it is. If someone has a tricky way of biasing a coin, I’d be glad to hear about it. No need for money to complicate things. I don’t know that Einstein laid down money on relativity, but whether he did or didn’t isn’t relevant to the science.

That’s one way to look at things. The other way is that money aligns incentives.

Not targeting this specific case, but if academics had to bet, say, 10% of their salaries on replicablity of their work, there would be a lot less crap floating around.

What you didn’t realize is that this was actually part of a random email solicitation experiment about getting people to take bets on whether coin is unbiased or not. Or perhaps Piotr bet someone 20K that he could not get Andrew Gelman to take a bet, so offering you a bet he thought he could win 20K from was a way of covering his potential losses exactly.

Just wondering, why do we say *complete* stranger? Either someone is a stranger or not; we can’t have an incomplete stranger or a partial stranger.

Any linguists in the house??

I thought Shravan was a linguist!

I just thought I’d have some fun with it, watching non-linguists flailing about with modifiers and their meanings ;)

Some of us tend not to think in black and white terms. So degrees of stranger-ness makes sense to us.

Then there’s the connection with the other meaning (“peculiar”) of strange. And the connecting ideas of “unusual” or “unfamiliar”. Unusual, peculiar, and familiar make sense (to me at least) as being qualifiable by degree.

> … we can’t have an incomplete stranger or a partial stranger.

There are no partial strangers, only incomplete friends we haven’t met.

If you see someone commonly in some venue — for example, if you go to the gym at the same time — but have never spoken to them, then they’re a stranger, but not a complete stranger.

So from this we may conclude that your paper is wrong.

Or you can read the paper: “The biased coin has long been part of statistical folklore, but it does not exist in the form in which it is imagined.” In the context of the paper the claim is fairly clear in that it presents a classroom exercise in weighting/biasing coins (and notes issues with flipping and spinning). If you want to step outside that context then it is fairly easy to bias a coin (e.g., a double-headed coin with a bit of sleight of hand).

But why not make this a condition of publication for empirical results? Authors have to specify the odds they’d lay/take & how much they’d be willing to bet on replication of their results? Put $ where mouth is.

Obviously the scheme would be distorted by differences in researcher wealth & liquidity. So every researcher could start w/ an endowment of, say, $1 million. Over time, bad researchers would either bottom out or never publish. Good ones would publish lots of papers & basically hover at some equilibrium slightly over $1 million (people learning not to take their bets).

I would also not take this bet. The scientists’ battle arenas are the journals, and I would not venture blindly into an unknown arena given considerable money at stake. If Piotr believes you’re incorrect, then he can conduct and publish his own experiments with his weighted coin disproving the claim that a coin cannot be made biased.

Piotr has put forth a false dilema: “either play my game, or your paper is wrong”, which could just as easily be flipped in the other direction from the other party “either publish a counter example, or shut up”.

This does not make sense, he will publish the counter example. The bet (or the Andrew’s denial of the bet) is actually part of the paper.

See details above. I think Andrew dodged ~$4M loss, no more complicated than cheap magnets and the right sort of coin.