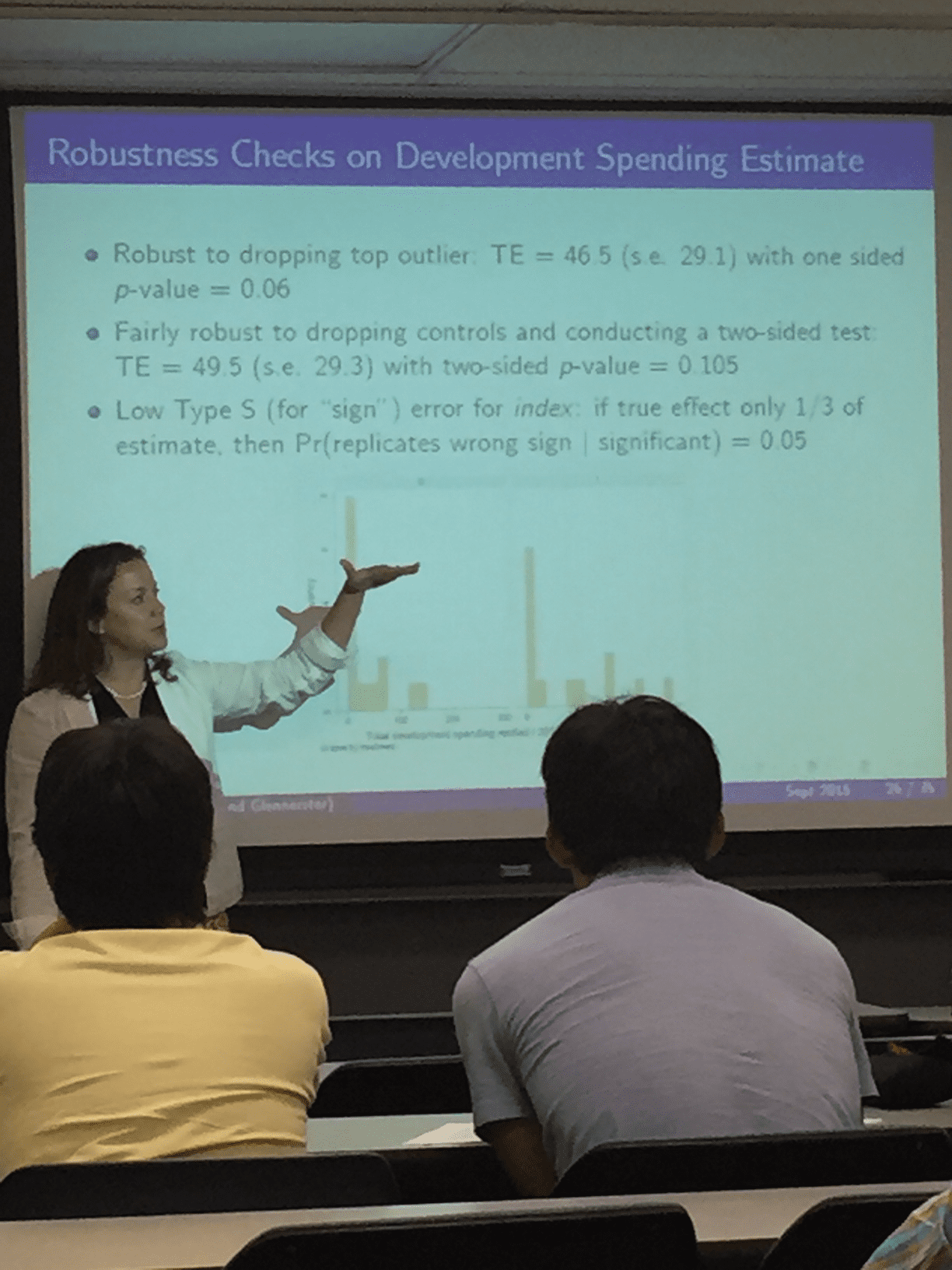

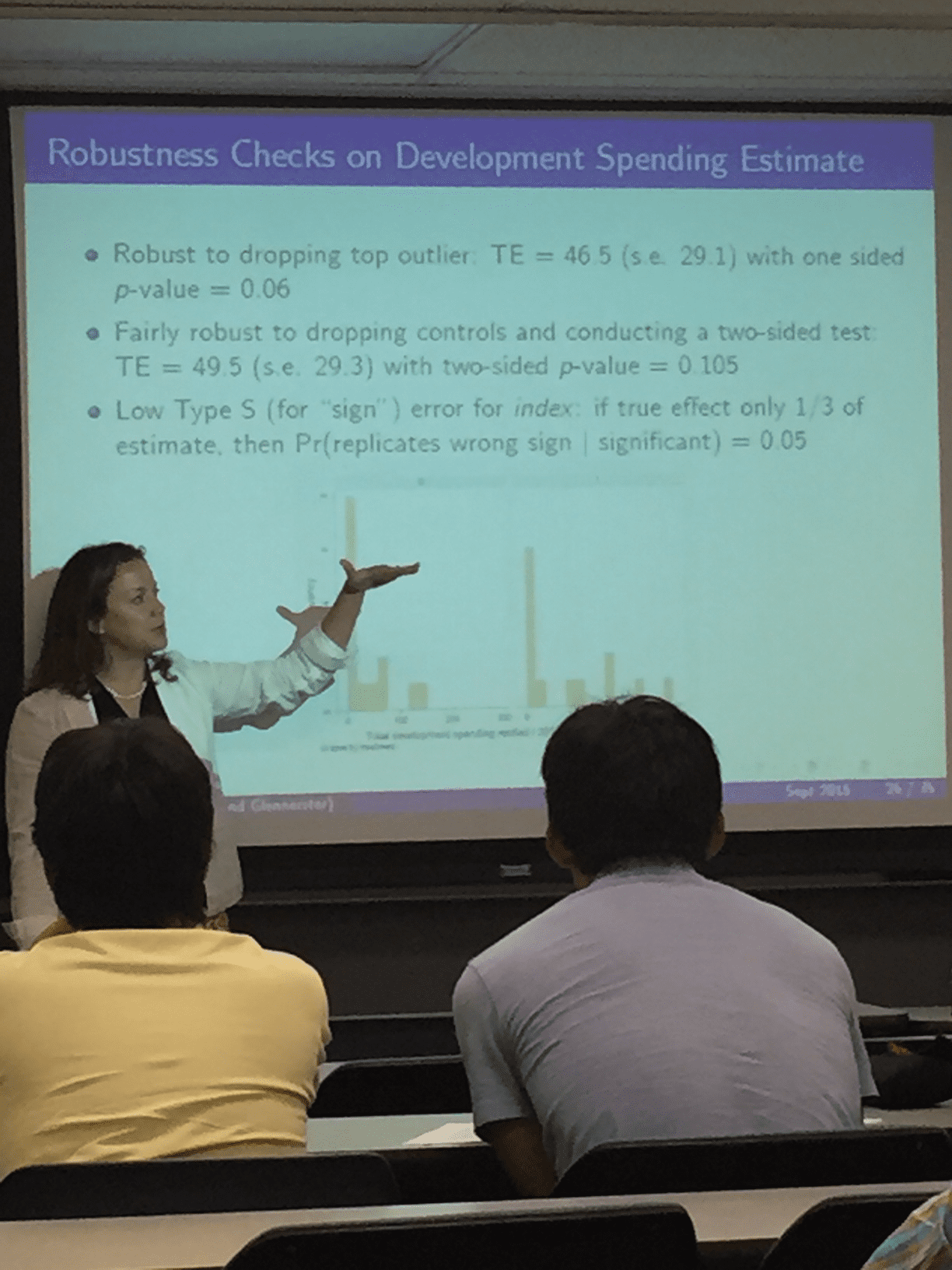

Kaveh sends along this, from a recent talk at Berkeley by Katherine Casey:

It’s so gratifying to see this sort of thing in common use, only 15 years after Francis and I introduced the idea (and see also this more recent paper with Carlin).

Kaveh sends along this, from a recent talk at Berkeley by Katherine Casey:

It’s so gratifying to see this sort of thing in common use, only 15 years after Francis and I introduced the idea (and see also this more recent paper with Carlin).

Sign errors are intuitive when the “null hypothesis” is not at the edge of the parameter space. What would be the equivalent thing to do when one has, for example, variance components that are restricted to non-negative and one would like to have some measure of “significance” or confidence of the estimate being away from zero? I guess one can always posit a minimum interesting size or compare with the magnitude of residual variance (or some similar parameter if available and reasonable). Are there some other measures that are standard?

Perhaps with something like variance the equivalent of sign error is “over estimate” vs “under estimate”?

I thought I understood the concept, but then I don’t fully understand (the point of) the slide so I’m obviously confused.

This type-S computation is data dependent, since the reference assumption is “1/3 of the estimate”.

But this can’t be true for any estimate, for e.g. what if your estimate was exactly zero (chance of type S must be 0.5)?

So I wonder if this means “assuming the estimate you got was itself of statistically significant size, e.g. at the edge of significance).” But isn’t the result kind of baked in anyway, up to distributional assumptions? E.g. assuming normality for 5% significance,

estimate is about 1.96 * se, reference value thus 1.96 * se/3, so wouldn’t the type S computation be

comparing the chances of seeing (> 2/3 * se) vs (-4/3 * se), which if I’ve computed correctly (probably not!) is about 0.05 anyway.

Correction, I mean 2/3 * 1.96, and -4/3 * 1.96, i.e. 1.31 and -2.61.

>This type-S computation is data dependent, since the reference assumption is “1/3 of the estimate”.

I don’t know but I would hope that by only seeing a snapshot of the presentation slide we are missing out on a cogent verbal argument for why “1/3 of the estimate” they happened to get with these data is, based on prior knowledge, a reasonable lower bound on the true effect size. That is, I would hope it is not really a data-dependent computation but rather a confusing way of presenting a non-data-dependent computation….

Thanks for pointing out the charitable reading, as well as the danger of inferring too much from one context-less slide :-)

But it’s fairly clear that the speaker is praising the “low” (0.05) value as good. It’s one of the three robustness checks given. Its value is called out (and even without more context, how can that be other than praise?) as low.

Well, if my calculations are right, it’s not low, it’s just what mathematics implies (under broad normality assumptions) if your reference is estimate/3.

So, trying to run with your charitable reading, what’s GOOD here is that the statistical procedure in use gave an estimate only 3x larger than some (hypothetically, proposed a priori) lower bound. That actually IS good; we thought the effect would

be of such-and-such order of magnitude, and the experiment concurred :-) I like that, though don’t think that restating this as a type-S probability adds any clarity. It’s good that you were close to your prior, does this need to be obscured so?

To put on my more cynical though, the word “only” is troubling. “if the true effect is only 1/3 of the estimate”. I think

your charitable reading is more like: we don’t think the true effect should be below X (some absolute value), and gee look,

our estimate is 3x that. But if we have to read into one slide, it sounds more like “our estimate is Y, and if we

construct a conservative lower bound far less, say only 1/3, of that…”. The word “only” strongly encourages

a post-data reading of the intent. IMO. But of course we don’t know.

Professer Gelman wants to promote the concept of Type-S errors. He has promoted this one (!) slide as an

illustration of how it might be catching on.

It’s kind of important to know – well, (a) this slide is a great example of the idea being used in practice, or (b) in fact,

the slide he choose to promote is conceptually 100% wrong as to the basic point. Option (c) I guess (is this your position Mr Bowman?) is: it’s just one slide, with no context, and could be fairly interpreted either way.

I contend that even if you see option (c) it merits a disclaimer/qualification relative to original blog title/content.

If I understand the type-S definition/rationale in the first place, and wanted to promote it,

I would not tout this slide. I may not be too distressed by it either but would quietly ignore it.

All this is conditional on: I’m not understanding something important. I have a reasonably high prior on the latter being false.

s/understanding/misunderstanding/ :-)

>Option (c) I guess (is this your position Mr Bowman?) is: it’s just one slide, with no context, and could be fairly interpreted either way.

Yes, that’s pretty much my position.

>So, trying to run with your charitable reading, what’s GOOD here is that the statistical procedure in use gave an >estimate only 3x larger than some (hypothetically, proposed a priori) lower bound. That actually IS good; we thought the >effect would

>be of such-and-such order of magnitude, and the experiment concurred :-) I like that, though don’t think that restating >this as a type-S probability adds any clarity. It’s good that you were close to your prior, does this need to be >obscured so?

I’m not a statistician (just a physicist), but I agree that under the scenario you’ve outlined stating a type S error probability doesn’t really add much clarity. Personally, the way I tend to use the type S/type M framework post-data is informally, i.e., as an aid to the critical assessment of claims in published research. The only time I’ve used the framework formally (and professionally) was pre-data in one of my service roles at my institution. It involved a group of faculty who wanted to use a budget I was partially responsible for to purchase standardized tests to use in a pre/post design in single courses. We had been giving this same test to both freshmen and seniors at the college for six or seven years. So I had a lot of between subjects data and a decent amount of within subjects data (not as much due to retention issues and the like) on effect sizes and variances with which to estimate a range of plausible true effect sizes for hypothetical single course designs (and analysis plans) as various fractions of the observed freshman to senior effect size. In this framework, the fractions of the previously observed effect size were actually thought of as upper bounds on a plausible true effect size that might occur in one of the proposed studies. Thus, I was able to calculate an upper bound on the associated powers and lower bounds on the type S error rates and expected exaggeration factors, all as functions of class size. In this way, I was able to convince myself and all parties involved that the measure was simply too noisy for their proposed purposes and that the money would be better spent on something else.

In retrospect, I guess these results did lead to a post-data use of the type S/type M framework as well. One of the people requesting the funds had actually used this standardized test at the classroom level in the past (the money came from another budget) and had been pretty discouraged that his innovative intervention did not show any gains for his students (he had been trained in the typical NHST framework and so interpreted a p greater than 0.05 as abject failure). So, this report I wrote showed him that the problem was not necessarily with his intervention but could have been his study design which I think (hope) was a real epiphany for him.

Anyway, I apologize for the tangent, but I thought that story would help clarify where I’m coming from and what I consider to be a good use of the type S/type M framework. Whether you, Professor Gelman, or anyone else agrees that it is a good use I leave for you, him, or them to say if so inclined. But I maintain that we don’t have enough information to say whether the use depicted in the above slide was a good one or a bad one. However, I agree it would be nice to have someone knowledgeable about this particular use case to comment.

Don Rubin (at his 70th birthday commemoration, at which some people video-phoned-in instead of attending) said something to the effect that he was most satisfied when researchers used his innovations so regularly that they no longer required explicit attribution. In this regard, congrats!

ST:

Yes, I’ve heard Don say this (although not at the meeting, since I wasn’t there, I just sent in a short video I’d prepared).

In this particular example, I think Type S errors are a new enough idea that I probably was cited. But I don’t really care either way. I just want people to be moving away from the traditional true/false hypothesis thing, and so I’m happy to see Type M and Type S errors in any form. It’s not about the credit at all.