Ben Lauderdale and Doug Rivers give the story:

There has been a lot of noise in polling on the upcoming EU referendum. Unlike the polls before the 2015 General Election, which were in almost perfect agreement (though, of course, not particularly close to the actual outcome), this time the polls are in serious disagreement. Telephone polls have generally shown more support for remain than online polls. Polls from different polling organisations (and sometimes even from the same organisation) have given widely varying estimates of support for Brexit. The polls do not even seem to agree on whether support for Brexit is increasing or decreasing.

This lack of agreement partly reflects the fact that polling a referendum is more difficult than a general election, because general elections occur regularly and many patterns can be expected to stay the same from election to election, enabling us to learn from past mistakes. Referendums address unique questions that may turn out different voters, and may scramble the political loyalties that tend to persist from general election to general election. Still, as the Scottish independence referendum showed, it is possible to get pretty close to the right answer with careful polling and analysis. In this article, we describe a strategy we are using to synthesise the evidence from the many polls that YouGov runs, the resulting estimates of the overall referendum results and how it breaks down by geography and some other variables – as well as what might still go wrong with our approach. . . .

More discussion and graphs at the link.

Full disclosure: YouGov gives some financial support to the Stan project.

__”…the fact that polling a referendum is more difficult than a general election, because general elections occur regularly..”

If one properly samples a defined population for a single variable (referendum issue X, Yes/No) — why would that be more technically difficult than individually sampling a lengthy time series of independent general elections (Candidates W/X/Y/Z, Yes/No) ?

The alleged high level of noise unique to referendum polling seems a rather lame excuse for deficient polling procedures.

Mort:

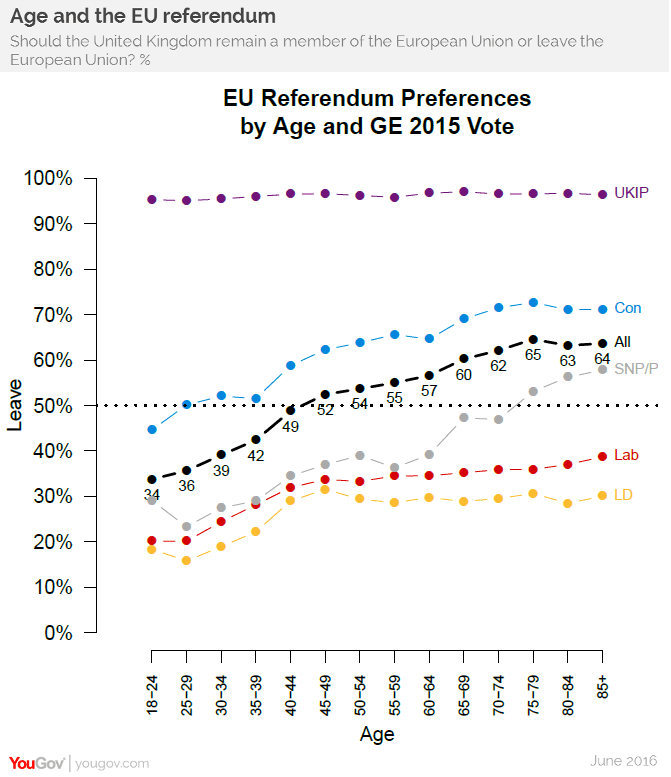

There are two ways in which a referendum differs from one in a series of general elections. The first is that attitudes can be more volatile: the referendum is something new, so it’s not like you can guess that I’ll vote Conservative because I voted Conservative in the previous election. The second is that, in a series of elections, the relative votes among different demographic groups and different geographic areas tend to be stable over time, even when there is a national swing. For a referendum you don’t have that sort of basis of comparison. The difficulties have to do with context. After all, we’re not really drawing balls from an urn; lots of adjustment is needed and that requires subject-matter knowledge.

Polling on referenda is more “difficult” than general elections because the “standing decision” has already been made in that type of election. The analogy that will help is to think of a referendum as more similar to primary than a general election, where there is no party identification to rely on. In particular, in the US, we haven’t had a blow-out election since 1984 in the presidential race, but there were blow-outs in 1932, 1936, 1964, and 1972. So predicting a close-election (within plus or minus 6-7 points) is the way to go in a general with the set partisan inclinations that have hardened over the last several decades. On the other hand, look at the polling for the Republican primary and how off it was.

I should mention is that one way a primary is different than a referendum is that there are multiple candidates and often there is trading off in the lead (as measured by polls) until (usually) several weeks before the end.

Numeric:

Regarding primaries and general elections, see this article that I kept sending to reporters during the past year: http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/29/why-are-primaries-hard-to-predict/

I have often wondered in some social choice settings whether the survey affords the participant the opportunity to register some disgruntlement that does not align with the more practical vote that same participant will will cast later at the ballot. So I respond to the survey that I will vote in favor of Brexit – Yay! Glad I register my general satisfaction somewhere, but for the actual vote that matters I will be more practical and vote against Brexit because I believe the economists who tell me that Brexit would be terrible. Binary choices between polar outcomes rather than candidates for election would seem to lend themselves to this model. Inconsistent poll results in the week before the vote would seem to support the possible validity of this interpretation.

To be clear, this rule would apply in particular in the case of a choice between status quo and radical change.

Still, as the Scottish independence referendum showed, it is possible to get pretty close to the right answer with careful polling and analysis.

The alternate argument is that YouGov was part of the polling-campaign complex and “spruced up” the dynamics to drum up business. Consider this plug from the yougov website:

In our poll at the start of September we showed the Yes campaign inching ahead. The poll electrified the campaign, dominated the media and resulted in the main party leaders abandoning PMQs to campaign in Scotland and making increased promises of devolution to try and save the Union.

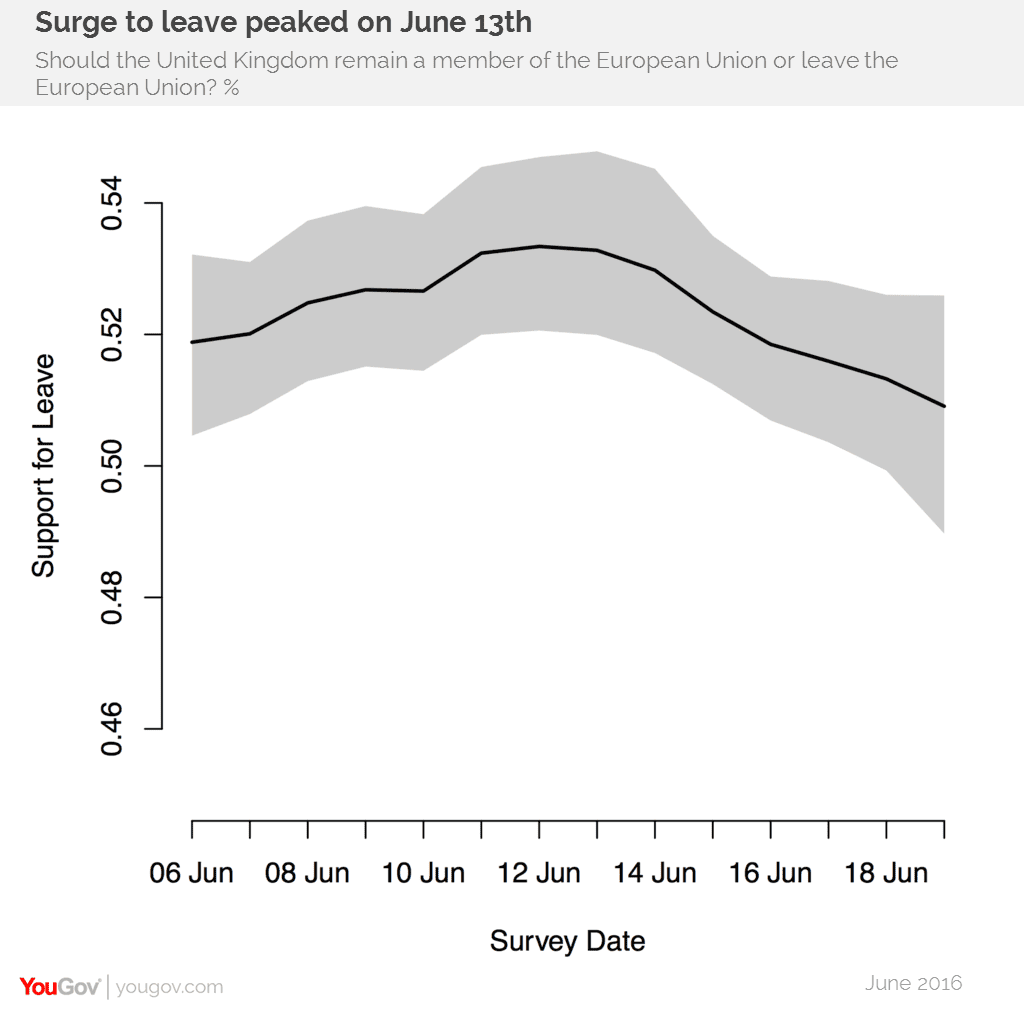

I still remember yougov getting the california 2005 special wrong when every other pollster got it correct. Now, maybe their methodology is better now (though the academic work was done by you and others in the 90’s as I recall). In general, averages of polls are empirically just better and the British don’t obsessively poll the way it is done in the US so I doubt that there are many other polls available, but if they are, is there any corresponding indication of a “surge” right before the election?

the disclosure’s a bit laconic; not exactly “full” …

Z:

I think this is a standard sort of disclosure. What do you think is missing?

Andrew:

I’m aware of this paper, data set, and R code to learn more on how to run MRP: http://www.princeton.edu/~jkastell/mrp_primer.html

Are there any other more resources you’d recommend in implementing MRP, particularly via R?